To better understand the different types of tomato diseases, we must organize a comprehensive table of diseases, making it much easier to detect and treat them early.

Once again, welcome to our Novamulch agricultural space. For this occasion, we invite you to review the first part of this article, in which we detailed the integrated prevention and control methods we recommend adopting beforehand. However, we will note here a few that we consider relevant for each case.

Here is the link to our part 1, hoping it can be of great help:

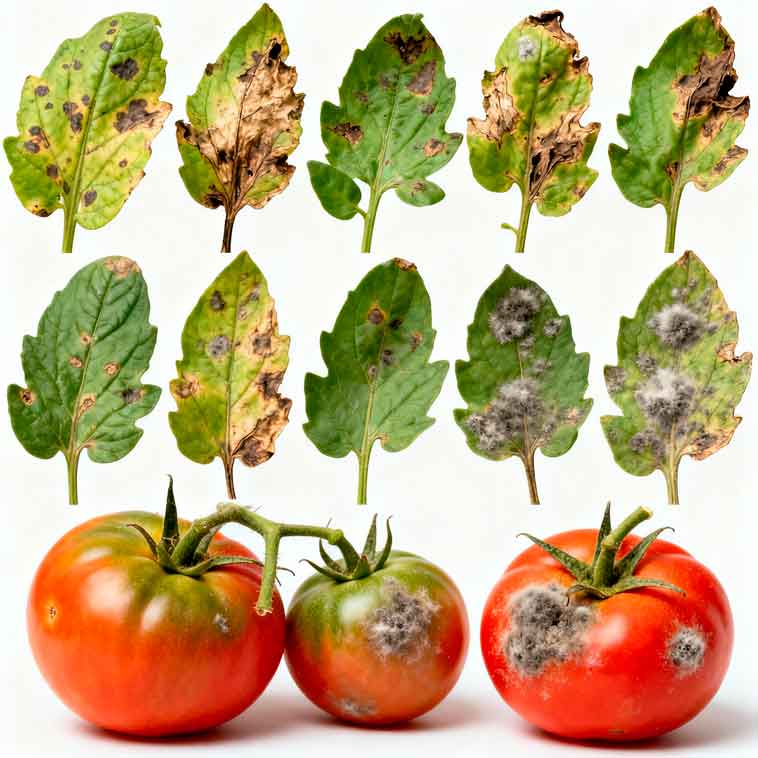

Classification of tomato plant diseases.

We present the following table to help you more easily identify tomato plant diseases. Let’s take a look.

Main fungal diseases in tomato plants:

Downy mildew (Phytophthora infestans).

Powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica).

Fusariosis (Fusarium oxysporum).

Alternariosis (Alternaria solani).

Main bacterial diseases in tomato plants:

Bacterial spot (Xanthomonas campestris).

Bacterial canker (Clavibacter michiganensis).

Soft rot (Erwinia spp.).

Main viral diseases in tomato plants:

Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV).

Yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV).

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV).

Transmission by vectors (whiteflies, aphids, thrips).

Let’s review this interesting information:

Fungal Diseases (fungi). One of the most common and destructive groups.

The main characteristics of these diseases are those shown below, and all of this means that we are dealing with pathologies that are difficult to eradicate if we do not act in time:

Ability to spread rapidly by spores. Sporulation of the fungus means it releases spores that are especially adapted to conditions of high humidity and moderate temperatures, forming a whitish powder or layer on the underside of infected leaves: a mass of spores ready to disperse, moving through air, water, and direct contact with adjacent plants.

They have a very rapid germination capacity and persist in nesting indefinitely both in plant residues and in the soil structure.

What are the main fungal diseases of tomato plants?

Downy mildew (Phytophthora infestans).

Observations prior to the appearance of visible symptoms of mildew.

Before the symptoms of mildew on tomato plants become clear, such as spots, necrosis, and sporulation, there are subtle signs we should be aware of in advance so we can act in time and prevent greater and perhaps irreversible damage to our crops. Let’s review them.

Weather and environmental signs.

When we experience persistent high humidity, above 90% (this is when spores develop and germinate), heavy dew during the night, and continuous rain.

Cool, temperate nighttime temperatures, between 10° and 20°C, combined with cloudy days and little sunlight. This prevents rapid drying of the foliage and creates a favorable habitat for the growth of these fungi.

Persistent shadows and poorly ventilated areas in our crops, particularly near hedges, greenhouse edges, or dense rows, where moisture is retained longer.

Presence of nearby inoculation sources, such as infected plant debris, tubers, or volunteer plants (tomato or potato), which are leftover from previous crops and will provide viable spores awaiting favorable conditions to infect.

Subtle changes in plant state.

When young leaves or apices show slight wet marbling or mottling, even before marked spots appear: slightly darker areas with a watery appearance in humid conditions and barely detectable to the naked eye.

Delayed growth, slow development of new leaves due to the physiological stress caused by the early infection, and microlesions that are almost imperceptible to the naked eye. This means that the fungus appears in latent conditions with hidden sporulation but with intense and rapid activity.

By targeting the entire plant structure and keeping the leaves moist, irrigation creates a perfect breeding ground for this fungus. This is why drip irrigation and the use of Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch prevent the development and spread of this type of tomato disease.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by mildew on tomato plants.

The leaves have irregular spots. Initially, they acquire a light green or olive color, and then develop a moist appearance toward dark brown or blackish tones.

Under conditions of high humidity and moderate temperatures, the underside of the leaves becomes covered with a whitish veil or cottony powder, indicating sporulation of the fungus (phase in which the fungus produces and releases spores ready to disperse through the air, rain, direct contact and sprinkler irrigation, generating new infections in the plants and spreading to adjacent ones).

Elongated, brown to black necrotic lesions appear on the stems and petioles and generally surround the stem, causing the plant to collapse.

The fruits show brown or glassy spots with an irregular contour starting from the calyx area, and then they sink, causing rotting of the internal tissue.

As leaf lesions spread, the plant quickly sheds its leaves, reducing its photosynthetic capacity and vigor.

In severe cases, the vascular system collapses. This means that stem lesions disrupt sap flow and cause wilting or death of the upper shoot.

Infected fruit rots, developing sunken spots and soft tissue. This can destroy entire crops in a very short time, as the fungus spreads rapidly. The fungus anchors and persists in the soil and plant debris, which will be highly detrimental to subsequent planting seasons.

Let’s review the effective measures we can take to prevent mildew from appearing on our tomato plants. Important note: We must act before the symptoms we’ve already discussed appear.

We already know that this fungus requires high humidity levels and wet foliage to germinate and sporulate, so cultural practices that reduce humidity are essential.

We’ve reviewed the recommendations for rotating our crops, removing all remnants from previous plantings. We’re also going to choose both resistant varieties and non-solanaceous species to break the fungal cycle. Let’s study.

In the area where we have planted tomatoes, potatoes, eggplant, peppers, chili peppers, and tobacco (solanaceous), we must grow the following non-solanaceous species:

Leafy vegetables. Their cycles are short and they help clear the soil:

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa).

Escarole, Endive (Cichorium endivia, Cichorium intybus).

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea).

Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris var. cicla).

Root and bulb vegetables. The following are not hosts for Phytophthora infestans:

Carrot (Daucus carota).

Beetroot (Beta vulgaris).

Onion (Allium cepa).

Garlic (Allium sativum).

Legumes. They provide nitrogen to the soil, improve its fertility, and interrupt the fungal life cycle:

Green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris).

Pea (Pisum sativum).

Broad beans (Vicia faba).

Cereals and grasses. They are very effective at renewing soil structure, especially against the fungi that invade solanaceae:

Sweet corn (Zea mays).

Wheat, Barley, Oats (depending on the agricultural system).

Cruciferous vegetables (brassic vegetables). They release natural compounds that produce a biofumigant effect:

Cabbage, Broccoli, Cauliflower, Cabbage (Brassica oleracea).

Practical recommendations to avoid diseases in tomato plants (mildew):

Rotate plants for at least 3 to 4 years before repeating planting solanaceae in the same environment, and alternate botanical families, that is, never plant species from the same family that are susceptible to sharing pathogens.

Powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica).

Observations prior to the appearance of symptoms and warning signs.

Let’s review the signs prior to the appearance of powdery white spots on our tomato crops:

Climate and environmental signs.

Moderate to high relative humidity levels, as powdery mildew thrives in habitats with sustained humidity, generally between 50% and 70%, and does not require leaves to remain wet.

Mild temperatures on warm days and cool nights. These are ideal conditions for spores to germinate.

Low direct sunlight and continuously shaded growing areas. Areas with low sunlight favor the survival of the fungus’s surface mycelium.

Insufficient air circulation due to densely planted crops, closed borders, or poor ventilation. These conditions create humid microclimates, which are highly conducive to the development of powdery mildew.

Subtle plant changes.

Presence of pale circles or slightly yellowish areas on the upper surface of young leaves. In these areas, the plant tissue weakens before the white mycelium becomes visible.

Young shoots grow deformed or weakened. In these cases, the fungus begins to interfere with physiological processes long before the appearance of mold is noticed.

A light, barely perceptible powder at the points where leaves meet or on the underside. We can see it more clearly with a magnifying glass. Here we may be looking at spores or incipient mycelium, moments before spreading widely and rapidly.

Nutritional stress or excess nitrogen. Plants with excessive and lush growth are more susceptible to this fungus and to fungal attack in general.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by powdery mildew on tomato plants.

Powdery white spots:

The clearest sign is the presence of a whitish, cottony, powdery mycelium on the surface of the leaves, especially on the upper surface. This powder contains the fungal spores; they are visible to the naked eye and easily come off when touched.

Yellowing and localized chlorosis:

Along with or surrounding the mycelium, the leaves show diffuse yellowish areas that then expand. The affected tissue weakens and becomes more fragile.

Necrosis and defoliation:

If the infection progresses, the yellow areas evolve into brown necrotic lesions, the leaves will dry out and fall prematurely, leaving the plant unprotected.

Reduced growth and vigor:

The fungus limits the photosynthesis process, causing general weakness of the plant, and young shoots appear stunted and develop slowly.

Fruit damage:

These cases are less common, although in severe attacks, powdery mildew can reach them, causing whitish surface spots or loss of shine. It doesn’t always rot them, but it does reduce their commercial quality.

Let’s analyze the recommendations so we can avoid the appearance of powdery mildew.

Prepare in advance and maintain adequate aeration throughout the entire crop cycle. We will design planting frames and pruning to prevent moisture buildup, especially in the foliar system.

Drip irrigation is always more beneficial and appropriate for maintaining the balance of our plants’ structure and strength. Avoid excessive nitrogen applications, as this creates softer tissues that are more susceptible to fungus.

Fusariosis (Fusarium oxysporum).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

The visible symptoms of this fungus are wilted leaves with yellowish tones and vascular necrosis. But before these signs appear, we can detect indicative marks that indicate early Fusarium infections. Let’s study.

Subtle physiological and vegetative signals.

Partial wilting. During the warmer part of the day, some branches and leaves may show signs of mild wilting, although the plant may show signs of recovery during the night. This symptom fluctuates and indicates that water flow is partially compromised.

Chlorosis in lower leaves or on one side of the stem. This means that before the entire plant is affected, it’s common to observe yellowing of older leaves or those on the sides, which may be due to a partial blockage of the vascular system.

Slower development or stunted growth. Here, the plant may show less vigor than other plants and produce new shoots that are shorter or have smaller leaves.

A feeling of dryness or unusual water deficiency, as even when the soil is moist, the plant may adopt a slightly more rigid posture, as if it cannot absorb water properly.

Internal browning of the basal stem. This sign precedes the visible and clearly noticeable symptoms. When we make small longitudinal cuts at the base of the stem, or neck, closest to the ground, we will observe a slight brownish discoloration in the vascular tissues.

Fusarium usually invades from the roots; it’s a silent infection. Some of the initial damage can occur underground: weakened root tissue, death of root hairs, or microlesions that begin without appearing in the aerial parts.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by Fusarium wilt in tomato plants.

This is one of the most destructive tomato diseases. It develops primarily through the roots and progresses by blocking the plant’s blood vessels, causing progressive and extensive wilting. Therefore, crop rotation is essential to prevent remnants of this fungus from persisting (for years) and affecting future agricultural projects.

Alternariosis (Alternaria solani).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

When our agricultural roadmaps are based on temperate to warm climates, between approximately 24° and 30°C, and with episodes of intermittent humidity such as dew, light rain, fog, combined with dry seasons (which benefit the germination and dispersal of spores), we are in the presence of an ideal breeding ground for this pathogen to develop and spread.

In these cases, the inoculum will generally remain on the residues of tomato, potato, and other solanaceous species, and if frequent splashing occurs in our crops, soil droplets can project the inoculum to the lower leaves.

Vegetative changes and subtle signs.

Small, dark spots with concentric rings on the leaf surface closest to the ground. Older leaves may have small, dark brown spots with surrounding yellowish areas. This is where the fungal lesion begins to progress.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by Alternariosis in tomato plants.

The lower branches develop less vigorously and slowly. Micro-lesions appear on the veins, which the fungus exploits to penetrate the system, almost imperceptible to the eye. Progressive defoliation begins, as massive leaf infection reduces the photosynthetic surface, weakens the plant, and leaves it vulnerable to sunlight.

The tissue of the plant’s overall structure dries out in small areas, and this is not due to water stress but to incipient internal damage.

Alternaria disease in tomato plants, also known as early blight, is caused by the fungus Alternaria solani and primarily affects leaves, stems, and fruits.

Specifically, on the stems, elongated, sunken, dark lesions appear, weakening the tissues and hindering the transport of water and nutrients.

Fruit deterioration usually begins near the calyx, appearing as sunken, dry, dark-brown lesions with visible concentric rings; the fruit can become hard, rendering it unmarketable due to its poor quality.

We show some interesting information about Alternaria:

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternaria

What role does biodegradable paper mulch play in combating fungal diseases in tomato plants?

It is essential to implement the use of biodegradable paper mulch in these cases, as it acts as a physical barrier, preventing the action of water splashes and infected soil particles, ideal vehicles for the spread of fungal agents. It also considerably reduces humidity around the base of the plant and, as we have already analyzed, will create a microclimate antagonistic to the development and spread of Alternariosis.

Adding Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch is an effective alternative, as it naturally biodegrades at the end of each crop, converting it into a rich nutrient. Furthermore, since it prevents the growth of fungi and weeds like sedge, the soil structure will remain free of infestations.

Once again, Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch works as an essential agent in these cases, helping us prevent uncontrolled evaporation in the soil. This material reduces relative humidity levels around each plant and prevents the lower leaves from coming into contact with the soil.

In this way, Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch creates a protective and harmonious microclimate that inhibits the development of this fungus and all tomato plant diseases.

You can purchase Novalmulch Biodegradable Paper Mulch here:

-

PACK of 6 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 120 cm. x 300 m. (1.800 m)565,28 € VAT included

PACK of 6 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 120 cm. x 300 m. (1.800 m)565,28 € VAT included -

PACK of 3 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 120 cm. x 300 m. (900 m)282,22 € VAT included

PACK of 3 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 120 cm. x 300 m. (900 m)282,22 € VAT included -

PACK of 6 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 60 cm. x 300 m. (1.800 m)282,22 € VAT included

PACK of 6 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 60 cm. x 300 m. (1.800 m)282,22 € VAT included -

PACK of 3 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 60 cm. x 300 m. (900 m)141,30 € VAT included

PACK of 3 rolls of Novamulch Professional paper 60 cm. x 300 m. (900 m)141,30 € VAT included -

Novamulch Professional Paper 120 cm. x 300 m.94,21 € VAT included

Novamulch Professional Paper 120 cm. x 300 m.94,21 € VAT included -

Novamulch Professional Paper 60 cm. x 300 m.47,10 € VAT included

Novamulch Professional Paper 60 cm. x 300 m.47,10 € VAT included -

Novamulch paper 120 cm. x 20 m.41,63 € VAT included

Novamulch paper 120 cm. x 20 m.41,63 € VAT included -

Novamulch paper 60 cm. x 20 m.21,89 € VAT included

Novamulch paper 60 cm. x 20 m.21,89 € VAT included -

Novamulch paper 60 cm. x 10m.14,85 € VAT included

Novamulch paper 60 cm. x 10m.14,85 € VAT included -

Novamulch agricultural mulching machine

Novamulch agricultural mulching machine

What are the main bacterial diseases of tomato plants?

Soft rot (Erwinia spp.).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

As in the previous cases, the ideal conditions for the proliferation of these diseases are habitats with high levels of humidity, as well as wounds resulting from handling, pruning, or insect intervention.

Soft rot begins to colonize more vulnerable tissues, and we can detect it by a slight loss of turgor in the basal stem or lower leaves during the hottest hours, even though these regain their firmness at night.

Moist or translucent areas or soft spots may appear near wounds or cuts, and in developing fruits, we may notice a slight softening near the calyx. This will occur before the lesion becomes visible.

Let’s see this information about White Rot

Visible symptoms and damage caused by soft rot in tomato plants.

This disease rapidly degrades tissues and reduces photosynthetic capacity, producing watery decomposition that can compromise the entire plant and fruit. The first visible symptoms usually appear on the stems and petioles, with areas that take on a moist, translucent, and shiny appearance, resembling waterlogged tissue.

As the infection progresses, these areas collapse; they become soft and grayish-brown, emitting unpleasant odors characteristic of bacterial decomposition.

The main stems show progressive wilting, starting at the base and spreading to the rest of the plant structure; here too, this bacteria interferes with the natural flow of sap. If we cut the stem, we will see brownish discoloration and a watery consistency, indicative of active bacterial necrosis.

Affected fruits show sunken, watery, soft areas that expand rapidly from the calyx, in wounded areas or where insect bites occur. In advanced stages, the tissue completely decomposes, releasing a cloudy liquid and a strong fermentation odor.

The fruits lose firmness and shine; they become dull, slimy, and, of course, worthless. This can destroy much of the yield in just a few days, especially when accompanied by high temperatures and excessive humidity.

After harvests, the bacteria continue to develop during storage and transportation, causing severe economic losses due to rotting of seemingly healthy fruit at the time of harvest. It can also persist in crop debris, soil, and irrigation water, acting as a source of reinfection for subsequent agricultural projects.

Bacterial spot (Xanthomonas campestris).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

Let’s detect these warning signs that may appear in our tomato plants to apply immediate preventive measures such as restructuring ventilation channels, using smart irrigation (drip irrigation), disinfecting the tools we use every time we work on our crops, and eliminating any plants that show mild symptoms.

The foliage area may appear damp with slightly translucent or shiny tissue in certain areas.

Very small spots or tiny spots appear in light green or yellowish tones with watery edges, similar to the internal moisture we see on young leaves and foliage close to the ground.

We can also detect diffuse yellowing in the lower foliage of the plant structure and in areas where leaves are in contact.

When touched, the leaves feel fragile and have a finer texture. This reflects internal stress that the bacteria is beginning to generate, even without visible necrosis.

Insect interaction, wind, or crop management can produce microcracks or minor wounds. This provides an easy entry route for the bacteria, without causing more significant symptoms in the plant structure.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by bacterial spot in tomato plants.

In the foliar system.

Small, dark brown or black spots, often with yellow halos around them, in the form of circles or angles, which can progressively degrade, detach or collapse, leaving perforated areas or a threadbare appearance in the leaf tissue.

These lesions may coalesce and form larger necrotic areas, and in severe cases the leaves will turn yellow, dry out, and remain attached to the plant structure as dead foliage.

On stems and petioles.

When the lesions extend to this part of the plant, they cause elongated, necrotic, reddish or dark brown spots, and at advanced levels the damage impedes sap flow, severely weakening it.

In the fruits.

When we notice that our green tomatoes have slightly sunken spots with moist edges, sometimes with a translucent halo of moist tissue. These spots evolve into more general, depressed, scaly, brownish or black lesions. While the lesions won’t penetrate deeply into the fruit, they will alter the appearance and commercial quality by forming superficial scales or craters.

Bacterial canker (Clavibacter michiganensis).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

This pathogen is characterized by invading the vascular system of leaves, and its ideal habitat is high humidity, especially when our tomato plants have wounds or recent cuts from pruning, plant manipulation, or insect intervention. This must be addressed as soon as possible, as the risk of infection will be much greater because the bacteria easily penetrates through all these openings.

We can detect the presence of the bacteria in our young plants and in the transplant phase before the lesions become visible, when their growth is weak, the overall structure is reduced, and there is temporary wilting of the branches.

We observe thin leaves with slightly necrotic areas or yellowish tones, and in this initial phase the lesions are not clearly defined.

In the case of tomato plants grown in greenhouses or after infected transplants, this disease remains latent and unnoticed for weeks or months before expressing classic symptoms.

If we make very thin cuts in the basal stem, we might detect a slight pale brown discoloration before the external symptom manifests.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by bacterial canker in tomato plants.

Keep in mind that bacterial canker can spread through seeds, reused tools that have not been washed or disinfected beforehand, and irrigation with contaminated water. This affects all planting environments, from crops grown on large areas to smaller spaces such as greenhouses, home and urban gardens, terraces, balconies, and pots.

We’ll see general wilting on the leaves. This is one of the most characteristic signs, and it begins by affecting only one side of the plant’s structure or leaf. This sign will gradually spread to the rest of the foliage.

If the edges of the foliage turn yellowish and then brown, creating a typical burn pattern, we are dealing with marginal necrosis.

In more advanced stages, the lower leaves will curl upwards, drying out and remaining attached to the stem.

On young leaves, small spots may appear in a dark brown tone with a yellowish halo, similar to those of bacterial spot, but drier and more angular.

The stems show elongated, dark brown or blackish lesions, occasionally accompanied by cracks or bacterial exudates. A longitudinal section reveals a brown discoloration in the vascular system; a typical symptom of internal infection.

In advanced stages, the stem may develop cracks that weaken its structure and obstruct the flow of sap.

Green fruit develops whitish spots surrounded by a dark halo, known as bird’s eye spots: distinctive of bacterial canker, and as the fruit ripens, these spots become more visible, and we will see depressions in the fruit skin and a rough surface.

In severe cases, the fruits crack, become deformed, lose their shine, and thus drastically reduce their commercial value.

Especially in young infected plants, flower and fruit production decreases considerably, and this can cause losses exceeding 80% if the pathogen invasion is not detected in time.

Some wise measures to consider when bacterial canker appears:

What role does biodegradable paper mulch play in combating bacterial diseases in tomato plants?

As we’ve analyzed, this material acts as a physical and sanitary barrier between the soil and the plant. It drastically reduces this risk by preventing infected soil from splashing onto the lower leaves, especially during irrigation or heavy rains.

In addition, it helps maintain a more balanced humidity in the root environment, avoiding excess water that encourages bacterial growth.

Its opaque surface also helps limit the germination of weeds such as sedge, which often act as secondary hosts for the pathogen.

Unlike conventional plastic mulches, Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch degrades naturally at the end of each growing cycle without leaving any residue, allowing for a clean, sustainable production system compatible with organic farming programs.

As part of a preventative management approach that combines responsible crop rotation, proper and continuous disinfection of tools, and humidity and irrigation control (preferably drip irrigation), it represents an essential tool for reducing the incidence of bacterial canker, for example, and protecting the overall health of our crops.

What are the main viral diseases of tomato plants?

Let’s look at two of the most serious tomato plant diseases that cause almost irreversible damage if not treated promptly. Let’s see.

Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

Here we may be witnessing slow growth or discreet dwarfism and the young stages of the crop, even before specific visual alterations appear.

A uniform yellowish coloration or slight pallor is generally observed on the youngest leaves, without yet showing a clear mosaic pattern. Mild environmental conditions favor early spread, such as intermediate temperatures around 24°C, and cloudy days or days with less sunlight, as this prevents the foliage from drying quickly.

Factors that promote the spread and contamination of this and all bacteria include the use of contaminated seeds, infected transplants, and inadequate mechanical contact, such as reused tools, hands, and clothing that has not been properly cleaned. All of these are sources of initial inoculum, especially when plants are frequently handled in the stages prior to the onset of symptoms.

Slight deformation or irregularity in new leaves, such as slight curls or slight undulation, can anticipate the presence of the virus and the impairment of cellular development, before the classic mosaic becomes visible.

Under latent inoculum conditions, viral particles may be lodged in the vessels or cells of the foliage without immediate external manifestation, waiting for favorable conditions to express themselves.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV) in tomato plants.

This virus is one of the most resistant and difficult to eradicate in tomato plants. It is highly contagious and easily transmitted through infected seeds, contaminated tools, plant-to-plant contact, and human handling. It can persist in tomato crops for months, severely affecting fruit productivity and quality.

The leaves show characteristic symptoms such as irregular, mosaic-like spots, combining dark and light green areas, especially on younger leaves. We can also detect deformations and curling, giving the leaves a fragile, stiff, or leathery appearance.

In the early stages of infection, upper leaves appear mottled or variegated, while older leaves show necrosis at the edges or between veins.

Severe infections show a reduction in leaf size and, in general, stunted plant growth.

Stems become thin and brittle, with shorter internodes, resulting in compact or stunted growth. In advanced cases, the virus causes internal stem necrosis, especially under conditions of heat or water stress.

Flowers often abort before setting, reducing the number of fruits per bunch. The developed fruits show irregular yellowish or green spots and deformities in the epidermis. Occasionally, necrotic, rough, or corky areas appear, affecting their commercial appearance.

The fruit’s internal contents may become uneven, with hard or poorly pigmented areas, affecting flavor and uniform ripeness. As a result, this virus causes a severe reduction in average fruit weight and reduced organoleptic quality (color, flavor, texture), and losses of up to 50% of marketable production, especially if the virus spreads from early stages.

This is why we must continually maintain rigorous soil hygiene after harvesting, and carefully disinfect growing trays, tools, and structures in every agricultural setting.

Yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV).

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

This virus is transmitted by the whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) and can become dormant in the crop, causing serious damage if not detected in time.

One of the first signs of risk is an unusual increase in the whitefly population; when we observe a constant presence of adults on the underside of young leaves or their rapid movement when the foliage is shaken. These are indicators of potential transmission.

At transplant time, seedlings may show slight loss of vigor and irregular growth, even without any clear foliar symptoms. The new apical leaves appear paler green or yellowish, and may feel rough to the touch.

If the growing habitat we have designed is in moderate heat, between 25° and 30°C, and the humidity levels are relatively high, this virus will replicate more rapidly within the plant, which will accelerate the subsequent appearance of symptoms.

Once the infection has started, a slight asymmetry in the growth of young leaves may be observed during the first few days, or leaflets that partially fold downwards for no apparent reason.

In the case of an infection from transplants or contaminated neighboring plants, young leaves may show less luster and delayed growth, thus demonstrating early metabolic alterations caused by the virus.

These early observations will serve as signals for us to take preventive and monitoring measures, thus helping us to stop the spread of this highly aggressive and difficult-to-control virus.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV) in tomato plants.

We are facing a virus that can cause yield losses exceeding 90% in early infections, and the impact on our tomato crops affects our production, crop quality, and viability. Keep in mind that this is one of the most serious and destructive tomato diseases.

Young leaves are the first to show symptoms, turning bright yellow along the margins, while retaining deep green veins, creating a typical yellow curl pattern. The leaflets shrink, wrinkle, and curl upward or inward, giving the plant a compact appearance.

In the first phase of infection, yellowing begins at the top of the plant and progresses downwards. The leaves become more fragile, brittle, and have a rough or leathery texture to the touch.

In severe cases, apical growth stops completely, leaving the plant with a stunted and dwarfed appearance. Infected plants exhibit excessive and disordered branching, a phenomenon known as bushiness. Flowering is drastically reduced, limiting fruit formation. Those that do develop are small, deformed, with irregular ripening, and may show yellowish spots or pale areas due to impaired pigment synthesis.

Once infected, the plant remains a carrier of the virus throughout its life cycle, acting as a source of inoculum for other healthy tomato plants.

What role does biodegradable paper mulch play in combating viral diseases in tomato plants?

Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch plays an essential role in preventing and managing viral diseases of tomato plants, such as Tomato Mosaic Virus (ToMV) and Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV). Although these viruses do not develop directly in the soil, they do depend on environmental factors, insect vectors, and cultivation practices, which mulch helps control naturally and sustainably. Let’s study.

We’ve seen that Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch acts as a protective physical barrier between the soil and foliage, preventing contact with contaminated particles, infected plant debris, or water droplets that could contain traces of the virus. By keeping the base of the plant isolated from the soil, we reduce the risk of mechanical transmission during watering or handling.

Thanks to its reflective and opaque surface, Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch alters the visual behavior of these insects, making it difficult for them to navigate towards plants.

We already know that our Novamulch mulch helps maintain balanced soil temperature and moisture levels, preventing sudden fluctuations that weaken plants’ immune systems. A plant with less water and heat stress is naturally more resistant to viral infections and less vulnerable to attacks by transmitting insects.

Unlike conventional plastics, Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch generates no waste or microplastics. As we’ve already discussed, it integrates naturally into the soil after the growing cycle, becoming an excellent nutrient and maintaining a clean and balanced agricultural ecosystem, a fundamental requirement for certified organic production.

Overall, Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch is now positioned as an indispensable tool in integrated disease management for tomato plants, acting indirectly but highly effectively in reducing viruses and vectors. Its continued use helps maintain healthier, more sustainable, and more productive crops, ensuring natural protection against the main phytosanitary risks affecting tomatoes.

What are the main physiological and nutritional diseases of tomato plants?

Below we will review tomato diseases that result from alterations caused by adverse environmental conditions, inadequate irrigation management, and deficiencies of essential nutrients.

They are not infectious, but they still cause severe damage and losses to the production, quality, and vigor of our tomato plants. It is very important that we maintain balanced soil management, irrigation, and nutrition at the correct timing from the initial stages.

This explanation can be very helpful:

https://youtu.be/LRE459oKw10?si=nUURsn0mbR02rllz

Let’s study the main physiological and nutritional diseases of tomato plants:

Apical rot or apical necrosis of the fruit (blossom-end rot).

This is one of the most frequent alterations in tomato plants, and manifests itself in the form of dark, sunken and dry spots on the distal end of the fruit, that is, the one we observe at the bottom of the tomato when it hangs from the plant, and is the area with the lowest concentration of calcium, which is why it is more sensitive to water deficit, and is usually the part most exposed to environmental stress.

Blossom end rot occurs due to a calcium (Ca) deficiency in the fruit tissue and is aggravated by irregular irrigation and humidity, or excessive salinity. To this end, and based on pH measurements, we must evaluate possible excessive doses of nitrogen and ensure a stable calcium supply.

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

In the early stages of the crop, newly set fruit exhibits irregular or asymmetrical growth. Some may temporarily stop developing, while others in the same bunch continue to grow normally. This imbalance in fruit uniformity is one of the first signs of calcium imbalance.

When we detect a slight softening or dullness at the lower end of the fruit (distal end), and we feel that area as thinner and less turgid, this indicates that we are witnessing changes in internal cellular pressure.

Fluctuations in environmental conditions such as high temperatures, low relative humidity, and irregular watering create a perfect habitat for this disorder to develop.

Excessive rainfall combined with dry soil due to lack of irrigation leads to leaching of calcium and other essential nutrients, resulting in necrosis. Likewise, an unbalanced calcium supply causes water stress, which will be reflected in the foliage: young leaves curl upward, with pale or yellowish edges.

As we can see, calcium is vital for maintaining a healthy balance during the development of our tomato plants. A deficiency affects proper water transport within the tissues, causing a progressive loss of turgor. The plants will appear less firm during the hottest hours, partially recovering in the evening.

This symptom is often confused with heat stress, but it is actually a warning of internal physiological instability.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by blossom end rot or apical necrosis of the fruit in tomato plants.

The first visible sign will be translucent or water-soaked spots on the distal end of the fruit, which turn brown or black fairly quickly, then dry out, and the affected areas acquire a leathery texture and rotten appearance. This lesion can cover a few millimeters to a third of the fruit.

The most affected fruits are those that appear first, especially those in the first flower cluster, because they experience the fastest growth and require the greatest amount of calcium. This leads to an even greater nutritional imbalance.

We observe evident external necrosis; however, the damage can extend into the interior of the fruit. The affected tissue becomes necrotic, spongy, and unpleasant-smelling if secondary contamination by opportunistic fungi or bacteria occurs.

Affected fruits lose their commercial value due to their deteriorated appearance and, in many cases, must be removed before harvest. This can translate into losses of up to 30% of total production in crops without controlled humidity and balanced nutrition.

In addition to direct fruit losses, blossom end rot leads to inefficient use of our investments and costs—water, fertilizers, and energy—as the plant invests resources in fruit that will never ripen. In intensive systems, this type of physiological disorder contributes to soil imbalances if not properly corrected.

Cracking of fruits (cracking or splitting).

This disease originates when the fruit ripens under unstable conditions of humidity and temperature, that is, when water is absorbed after a period of drought or dehydration, and this is when the fruit cracks and breaks.

Observations prior to the appearance of fruit cracking symptoms in tomato plants.

Tomatoes show unusual size variations between consecutive days. Fruits appear to expand more rapidly after dry periods followed by heavy rain or irrigation. These variations are a clear sign of water imbalance that can herald radial or concentric cracking.

When the soil structure fluctuates between dry and saturated, the roots absorb water rapidly, generating a sudden increase in internal pressure in the fruit. Before cracks appear, the tomato may show a slight loss of surface shine, indicative of tension in the epidermis.

The epidermal tissue of fruits expands and contracts due to fluctuations between hot days and cool nights, and if these conditions are continuous, the fruits can develop a more rigid and less elastic cuticle, predisposing them to cracking.

Ripening tomatoes that continue to absorb excessive water often show slight bulges or bumps on their skin before splitting. This phenomenon is especially common in thin-skinned varieties or in crops where irrigation is poorly regulated.

Soils with excess nitrogen and deficiencies in calcium and potassium also predispose to cracking. Before cracking occurs, it’s common to see very large fruits with soft walls and loose skin, a sign of weakened cell structure.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by fruit cracking in tomato plants.

When we detect concentric or radial cracks around the stem or in the body of the fruit, loss of shine and irregular texture before the fissures open, it will be a sure entry for microorganisms that cause secondary rot, and therefore, cause a considerable loss of the commercial value of our production and a very short conservation time of the fruits after being harvested.

Nutrient deficiency disorders.

We’re dealing with one of the most common causes of tomato plant diseases: nutritional imbalance. Let’s look at a simple chart to help you take notes on your agricultural roadmap:

Lack of nitrogen (N) causes yellow leaves from the base and weak growth.

Magnesium (Mg) deficiency causes interveinal chlorosis, that is, yellow leaves between green veins.

Lack of potassium (K) causes burnt or dry edges on the leaves and poorly colored fruits.

Excess nitrogen causes excessive foliage growth and delayed fruit ripening.

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

The first signs of mineral deficiencies usually appear on the leaves and general growth of the plant.

Calcium (Ca) deficiencies cause new shoots to show irregular growth and young leaves to become deformed or curl downward.

Newly set fruit may show a dull sheen and less firm areas at the distal end, a clear precursor to blossom end rot.

Magnesium (Mg) deficiencies cause older leaves to show a slight diffuse yellowing between the veins before visible chlorosis occurs, especially in sandy soil conditions or excessive watering that will wash away all essential nutrients.

Potassium (K) deficiencies are detected by a dull green hue and decreased consistency in leaf tissue. Vegetative growth slows, and flowers may partially abort.

These early signs are more evident during periods of high metabolic demand, such as flowering and fruit set.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by nutritional deficiencies of calcium, magnesium, and potassium in tomato plants.

Calcium deficiencies cause deformed young leaves and fruits with apical necrosis.

Magnesium deficiency causes yellow leaves with green veins (interveinal chlorosis).

Potassium deficiencies cause dry edges on adult leaves and irregular fruit ripening.

We can observe a decrease in the overall development of the plant structure, including the root system. Fruits appear weak and have a very short shelf life after harvest. Fruit ripens very slowly, and the characteristic uniform red color is lost.

Sunstroke or sunburn.

Direct exposure to intense sunlight, especially in dry climates, or after excessive pruning without adequate irrigation and sufficient leaf cover to protect crops from sunburn, causes these burns, and the appearance of whitish or yellowish areas that later turn brown and leathery on the fruit.

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

The consequences of sunburn are not immediate. Days before it appears, subtle changes occur in the foliage and fruit color.

Leaf cover decreases, and fruit surface temperature increases, which we can measure with infrared thermometers. This way, we can prevent temperatures from rising above 38° or 40°C.

In this situation, plant tissue exhibits localized necrosis due to excess ultraviolet radiation and very rapid water loss.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by sunburn on tomato plants.

Fruits exposed directly to the sun develop whitish or yellowish spots, resulting in a loss of aesthetic and commercial quality. Furthermore, they become more vulnerable to secondary infections, and dehydration accelerates rapidly, especially in open-field crops.

Water and thermal stress.

Irregular and uncontrolled fluctuations in temperature and humidity significantly affect the physiology of tomato plants and cause premature flower drop, flower abortion, and fruit deformation.

Observations prior to the onset of symptoms.

These prolonged periods of drought or sudden temperature changes cause physiological changes that can be observed before the plant shows obvious damage. Let’s see.

Daytime wilt: Leaves droop during the warmer hours and recover at night; this is a clear sign of water imbalance.

Light leaf curling: This is a natural defense the plant has to reduce transpiration, which usually indicates excessive heat or low relative humidity.

Reduction in overall vigor: manifested in less turgid stems and less open flowers, and in these cases, flower abortions and less pollination will occur.

Likewise, violet or blueish colors are evident on the underside of the leaves due to the accumulation of anthocyanins in response to thermal stress.

These early signs prompt us to adjust irrigation, redesign ventilation in protected crop environments such as greenhouses, and implement biodegradable paper mulch from the initial phase to stabilize the overall habitat of our agricultural project.

Visible symptoms and damage caused by water and heat stress in tomato plants.

When we observe an upward curling of the foliage, wilting during the hot hours and temporary cessation of growth, flower abortions or drop of young fruits, and in some cases a purple coloration appears on the underside of the leaves due to the accumulation of anthocyanins.

Yields will be drastically reduced, fruits will be deformed and of very low quality, and there will be an imbalance in the absorption of essential nutrients.

What role does biodegradable paper mulch play in the fight against physiological and nutritional diseases of tomato plants?

Novamulch biodegradable paper mulch plays a crucial role in preventing physiological and nutritional diseases in tomato plants by creating a stable and healthy environment for root development and overall plant structure.

These diseases, such as blossom end rot, fruit splitting, and mineral deficiencies or heat stress, are not caused by pathogens but by water and nutritional imbalances, and can be effectively controlled through physical and sustainable soil management.

Novamulch paper mulch acts as an effective moisture-regulating barrier, reducing excessive evaporation and preventing sudden changes between drought and saturation, as it improves and maintains a balanced retention of water and essential nutrients. This water stability allows for continuous calcium absorption, a key element in preventing blossom end rot, one of the most common and damaging tomato diseases.

In warm temperatures, the light surface of Novamulch paper mulch reflects some of the solar radiation, while in cold climates, the dark side helps retain heat.

This thermal balance reduces the plant’s physiological stress, preventing flower abortion, delayed ripening, and sun damage, especially in open-field crops and in protected environments such as greenhouses.

Another function of Novamulch paper mulch is to evenly distribute irrigation, distributing nutrients throughout the soil, and ensuring the balanced assimilation of essential minerals such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium. This prevents sudden absorptions that cause fruit cracking and reduces deficiencies that cause chlorosis or dry edges on leaves.

We remind you that we have shared detailed information about this material in our Novamulch agricultural space, and we are pleased to share the link as support material:

We also believe that the information we have shared in this other article, regarding the wise use and conservation of water, can be useful as support material:

We also share our article on sedge, a fearsome weed that plagues crops, weakens and consumes nutrients, and is a perfect entry point for tomato pests and diseases, our topic today.

Conclusions and Final Reflections.

We’ve reviewed the various tomato plant diseases, one of the most difficult challenges to treat and one that drastically affects the quality, productivity, and profitability of our crops.

This is why having an agricultural roadmap and a crop log are essential to record all the previous and obvious observations of each anomaly, as well as the integrated prevention and control methods we’ve implemented for each case. In this way, we’re creating a resource for our future harvests.

Let’s always keep in mind that trial and error are also essential, so let’s record them in our log as positive learning experiences to perfect our farming techniques and controls.

The conscious use of water, proper distribution of nutrients, control of weed proliferation, and the use of biodegradable paper mulch, Novamulch, will be four of the pillars on which we will base all phases of our tomato plant development, following a sustainable program that respects our ecosystem.

We now have the information and tools to achieve controlled and healthy crops, and we will be pleased to see that our efforts have resulted in optimal quality and profitability.